The Participative Approach in Environmental and Sustainability Education

Abstract · The concept of a participative approach in the context of environmental and sustainability education (ESE) is introduced in the first chapter. In the beginning, the concept of the participative approach, its limits, and its various interpretations is briefly discussed. In this section, it is argued that instead of the simple teacher-students dichotomy, it may be more useful to analyse students’ participation using the wheel of power, which is shared with other stakeholders. This will provide examples of ESE practice when the participative approach cannot be fully implemented. Some of the pitfalls of implementation of the participative approach in the ESE practice are discussed in the second part of this article. Here, the chapter is based on research on the various ESE programmes that have been implemented in the Czech Republic. The main benefits of the participative approach are then summarised in the last section, in which the rationale behind the spread in the ESE practice is explained.

Introduction

One of the often-recommended strategies for environmental and sustainability education is to give students some level of control over their learning. Students are not tabula rasa – they have their own agenda and interests. Based on this, they are more intrinsically motivated to learn about some topics more than others. As a result, they can participate in decision-making on what they want to learn, what activities they want to engage in, or what methods they want to use to achieve agreed-upon goals. The idea of what is called the “participative approach”, “emancipatory approach”, “pluralistic approach”, “participatory teaching”, or “student-directed learning” is to share some level of power in decision-making in the educational process with the students (Wals, 2008, 2012; Rudsberg & Öhman, 2010; Læssǿe, 2010; deBoeve-Pauw et al., 2015). In practice, this idea will be challenged by the questions and dilemmas introduced in this chapter.

The first issue is the diversity of understanding around what the participative approach means. It is obvious that there is more than one model of sharing power between students and educators. Participation may also mean different things in different educational contexts. Secondly, there is a question of benefits of and barriers to the participative approach. Regardless of the possible inclination to share power with the students, the participative approach is challenging and may not always be the best choice. Furthermore, while the participative approach can be considered as an effective tool for shaping students’ competences, the teacher-directed approach may have its positive impacts on students as well. The aim of this chapter is to discuss the pros and cons of the approach. To state it openly: I believe that participative approach is one of the most salient environmental and sustainability education (ESE) strategies, and as such it should be promoted more in educational environments. At the same time, it’s important to remain aware of its limits in order to avoid its pitfalls.

Sharing Power with Students: What Does This Mean?

Hart’s model of participation

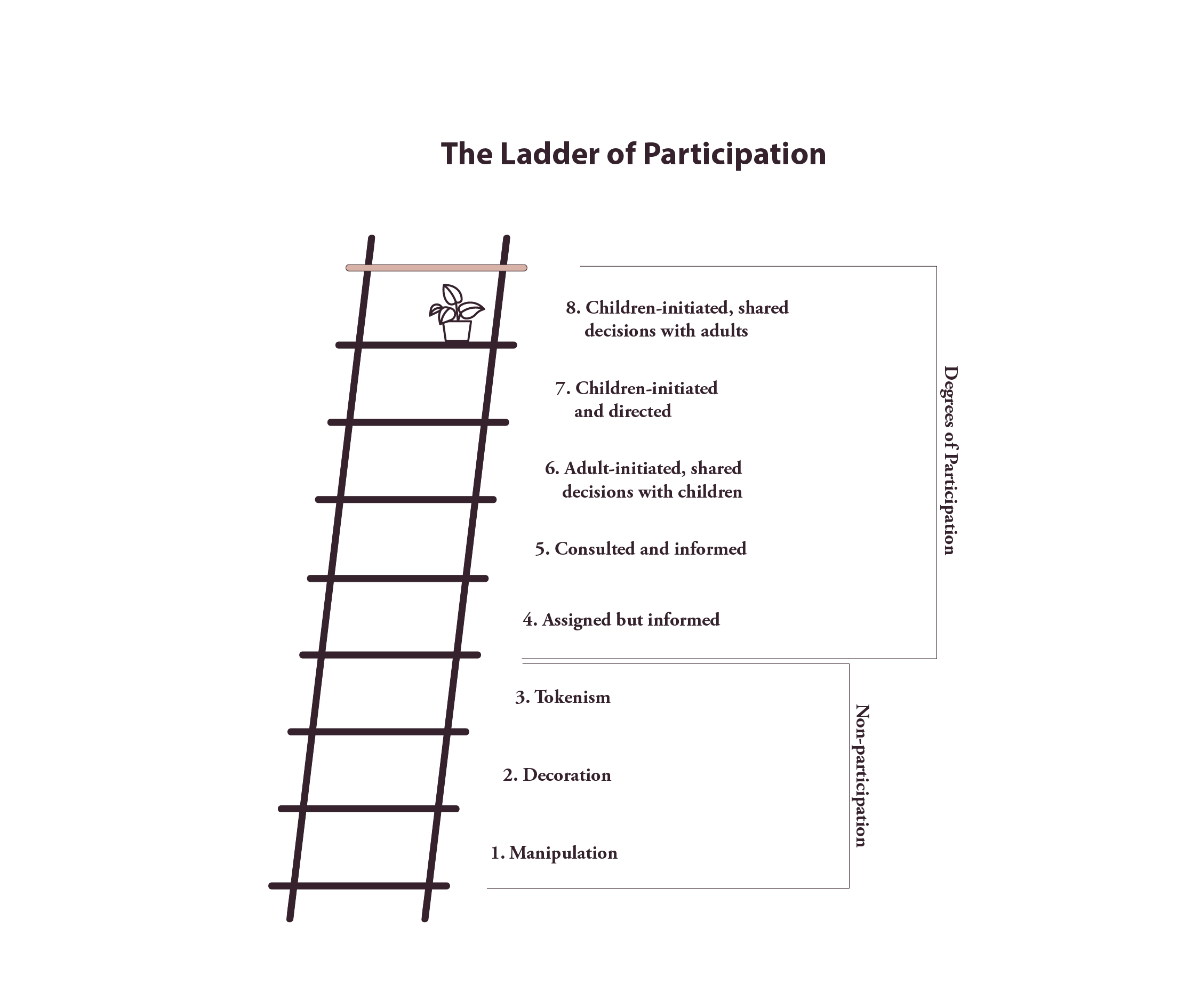

Hart (1992), in his well-known model, differentiates three false and five true levels of students’ participation. The higher the ladder ascends, the higher the degree of students’ participation will be (see Figure 1). There are a few interesting aspects of his model; for example, at first, while the model implies an idea of development, this was not its intention (Hart, 2008). Being on a higher level, however, does not necessarily imply a higher level of students’ (or teachers’) competencies. According to some of the authors, all five “true” levels may have a comparable merit, their choice may be a matter of specific context, and they may change in time or for another task (Ramey, 2017).

Furthermore, the model does not imply that full control for students’ will have the most mature effects. Actually, Hart presumes that the highest level of participation does not exclude adults, but rather accepts their distinctive roles and methods of sharing responsibilities for a project.1

The application of the model in the context of environmental and sustainability education may be both rewarding and challenging. The practice of ESE is diverse in terms of educational approaches, goals, programme formats, and methods; and an effort to aspire to the higher levels may not be always successful.

Too many cooks in the kitchen

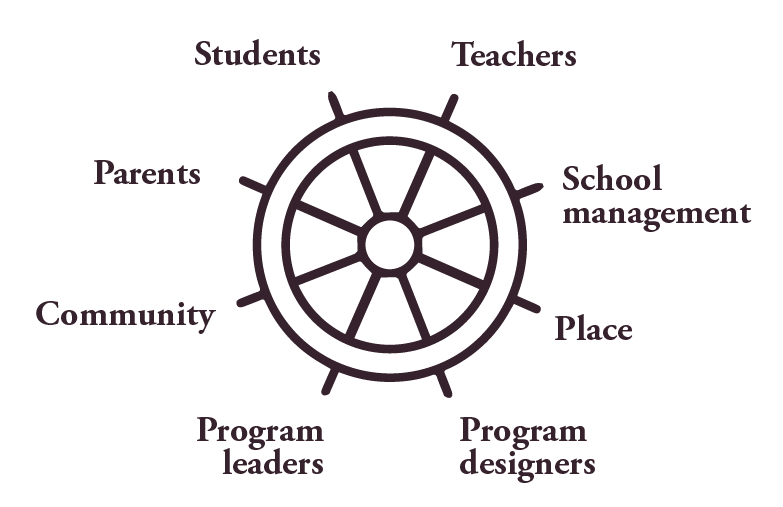

The first area to consider in the context of ESE is with whom the power should be shared. While some of the programmes may assume a simple teacher-student dichotomy, other stakeholders may be crucial for the success in other cases. When students are engaged in community projects, they need to negotiate their access to power not only with their teacher, but also with the representatives of the community; and it may mean including a variety of organisations, ranging from the local municipality to local non-profit movements. The residential nature of the programme can open a dynamic among students, teachers, and programme leaders; and sometimes, programme designers as well as – as some of the authors have mentioned – the place itself (Jickling et al., 2018).

From this perspective, the simple teacher-student dichotomy in defining the level of students’ participation may be too simplistic. Perhaps a metaphor of a wheel may work better, as an expression of which stakeholders can participate in decision-making in a programme. To merge both models together, each of the handles may be of a different length, indicating the level of stakeholders’ involvements (see Figure 2).

Brief, limited participation

While Hart’s model seems to fit with some of the ESE methods (e.g., with community or school-based projects), it may be difficult to apply it for other types of educational activities. Most ESE programmes offered by environmental education centres are quite short as they’re daily programmes that only last a few hours long; in such cases, students have a very low chance to influence the choice or the flow of the pre-prepared activities. The length of a programme seems to be an important condition for more meaningful student participation.

The residential programmes, which usually last between 3-5 days and are held outdoors, offer some opportunities for students’ voices to be heard, yet these programmes are also limited by their length. Generally speaking, high students’ levels of autonomy in outdoor programmes is recommended by several authors (Real World Learning Model, 2020; Kendall & Rodger, 2015; Menzies, Bowen-Viner, & Shaw, 2017); however, it is rarely used in practice (Menzies, Bowen-Viner, & Shaw, 2017). What can be observed is a mixture of three different strategies applied in these types of programmes:

- Responsibility for simple tasks: most of the residential programmes consist of a pre-prepared set of activities with the aim of achieving pre-determined educational outcomes. Students have very limited opportunities to influence anything. When given a task, however, they have the freedom to decide how to do it.

- Responsibility for complex tasks: in a few programmes, students’ autonomy levels were expanded to decision-making on complex activities, like what and how to investigate, where to go, how to present the findings, etc. While this approach assumes a considerable level of students’ participation, there is still no space for any decision-input on the programme design as a whole. There are the programme leaders or designers who – together with teachers – make the crucial decisions on the programme outcomes and main activities; while students have their part, they are still not real partners in the Wheel.

- Responsibility for the follow-up tasks: some of the outdoor environmental education programmes use a mixed approach. While students may have limited opportunities to influence the residential parts of a programmes, they may be granted substantial autonomy in deciding on follow-up, simple, or complex tasks; for example, students may leave the residential centre with a task to implement a community-based project of their choice, or a more-specific follow-up activity in their school (Činčera et al., 2020).

Generally speaking, different forms of ESE open different opportunities for the implementation of the participative approach. While it is a favourable option in some cases, it may not work well in others. From this perspective, students’ lengthy projects, based on their active engagement within their schools or communities, seem to offer the most suitable conditions for the participative approach. The long-term project format provides a space for learning from experience – the sequence assuming implementation of an action, reflection, analysis, and plan for the next steps. It also gives a group a chance to develop their competencies for planning, decision-making, organising, and evaluating the work.

Students Do Not Always Want To Be in Charge

The assumed benefits of student-control over learning processes and environments should not conceal the fact that sometimes students are not interested in taking these responsibilities and are happy when a programme is organised for them. This is particularly true for the outdoor programmes.

It’s evident in research focused on outdoor environmental education programmes that while some of the students appreciate when they have a chance to influence their programme, most students do not care much. They often interpret an outdoor programme as an opportunity to socialise with their peers and have a limited amount of motivation to decide on their outdoor learning processes. They appreciate if they have a lot of free time, and they like to use it for the social activities of their choice. Nevertheless, they also appreciate a well-prepared programme, facilitated by outdoor leaders; when they find it enjoyable, they are happy to engage with the learning activities and learn by playing (Činčera et al., 2020, 2021). A very different situation occurs, however, in examining the relationship between students’ satisfaction levels with long-term school projects and their perceived levels of participation. As in the case of the EcoSchool programme, the more students believe they have a chance to influence the decision-making processes in the project, the more satisfied they are with their involvement in the programme (Činčera et al., 2019).

Based on this, it is possible to conclude that the participative approach is crucial for some of the ESE approaches, particularly the longer school or community-based projects. It is not easily applicable in daily programmes, and it can be applied only up to a certain level in residential programmes. In addition, the idea of students’ participation levels should not conceal the role of other possible stakeholders, who may also exercise a degree of influence over the way a programme is shaped.

Why to Be Participative? Is It Restrictive?

Non-participation

As Hart (1992) suggested, not all possible measures of students’ engagement levels in a project represent their “true” participation efforts. Clearly, for residential programmes, many students were only provided with a limited opportunity to participate in decision-making processes. Teachers sometimes question students’ competencies in decision-making; for example, a teacher involved in the EcoSchool project defended his choice to direct the process and not allow students involvement in the decision making according to the following:

“If they [students] had to decide on their own, I think it would cause conflicts and one group would be angry with another that they decided it so, or that they were voted out, so it would bring discord to their cooperation.” (Činčera et al., 2019)

As a result, students’ autonomy levels are limited by their teachers when it comes to less or more complex tasks; for example, students may have a chance to decorate the dustbins in their classroom, but they are not supposed to analyse or question the way the waste management in their school works. In another case, students were asked to prepare educational activities for younger students for Earth Day, because it is a tradition and their school organises similar activities every year. At the same time, students have no choice to question that tradition or to come up with something new (Činčera & Kovacikova, 2014).

While this approach may lead to a lack of motivation for students, it is not always the case. When participation has no tradition at a school, students may not be aware of any other options; they may feel that even a small amount of participation is better than what they have been used to. If they genuinely like their teacher, they may be happy to follow their instructions. Paradoxically, the teacher-directed approach may frustrate more teachers than students (Činčera et al., 2019), and the opportunity for students to learn has been lost.

Fake participation

In some of the cases, teachers pretend to give their students a voice while they covertly manipulate the process. In the ESE context, it is sometimes apparent that the original intention of the participative approach degrades in other forms, like “fake” participation. Let’s look at the opinion of a kindergarten teacher involved in the EcoSchool project:

“I clearly believe it is important to listen to the children, but it is up to the adults to decide and gently manipulate the children to let them think it was their idea” (Činčera et al., 2017).

In this case, the teacher created the illusion of students’ opportunities to participate in the decision-making process on the design of their future schoolyard; however, the teacher had little faith in the students’ abilities to come up with a constructive idea. Instead, she pushed them to suggest her original idea and intention, as she was afraid that students would promote immature ideas, like having a TV set in the garden.

There are similar situations in many schools. One teacher decided to start a community-based project, but she was afraid that students’ ideas on what to change in the community may not be realistic; to mitigate this, she promoted an action that was either already planned by the municipality or had a supposedly non-controversial nature (Lousley, 1999; Činčera et al., 2019). While the idea to monitor the manageability of a project has its merit, these teachers appear opposed to the very nature of the concept of the participative approach. In facilitating an education, adults should be honest with their students – they can openly control them, or they can give them the right to participate, but they should not mask one for the other.

Lost control

A promising start of a participative process may not guarantee the same levels of students’ control over the whole project. At one of the school, for example, students decided to plant a new tree in the area they liked. While the idea was well accepted by both their teacher and the municipality, the adults decided that a new tree was needed more in another place. The municipality then organized for the tree to be planted, and the students were only asked to participate in final celebration of the event once everything was accomplished. After such projects, students had mixed feelings: they intended to initiate real change, but they lost their control over their projects (Činčera et al., 2019).

When we consider the question of distribution of power using the Wheel Model, rather than a ladder, we can also better understand why a participative approach may be reduced to the masked efforts of adults’ directions. Maintaining the participative approach throughout the whole project may be as important as giving students’ voices a role in project selection.

What to get from participative approach

Finally, we come to the benefits of the “real” participative approach in ESE. Considering all of the difficulties and possible pitfalls, why is this approach worth trying? To answer this, it is necessary to emphasise that the teacher-directed ESE programmes also may be highly successful. As discussed, the participative approach may not be necessarily suitable for all types of ESE programmes. The residential programmes often provide only a limited opportunity for students to participate while mostly the programme designers and leaders hold the Wheel. It can be argued that the lack of students’ participation in shaping the programme may endanger their motivation to be engaged. The residential programmes combat this by using a variety of tools to promote intrinsic motivations for students. Particularly, younger students may be more motivated by direct interaction with nature and animals, adventurous, enjoyable tasks, an atmosphere of mystery, or by other means. There is a vast array of evidence that highlights the positive impacts of residential programmes on students’ environmental knowledge, competences, attitudes, and even behaviours (Bogner, 1998, Baierl, Johnson, & Bogner, 2022, Bogner & Wiseman, 2004).

The participative approach may bring a significant additional value. Interestingly, when comparing the EcoSchool programmes kindergartens that applied the participative approach with those directed by teachers, we found that the children from the participatory kindergarten had stronger pro-environmental attitudes than the other group (Činčera et al., 2017). It may be even more important to consider the way that the participative approach influences students’ abilities to act. An opportunity to decide and see the results of their decisions is crucial for developing students’ action competencies (Činčera & Krajhanzl, 2013). Students only felt ownership over the implemented projects when they believed they had a chance to participate in the decision-making process – they felt the success was also their success (Činčera et al., 2019). As a result, the participative approach develops students’ beliefs they are able to promote changes for the environment through their own efforts (Kroufek & Činčera, 2021). This belief is, consequently, crucial for their pro-environmental behaviours and attitudes.

Conclusion

There are many ways of implementing sound environmental and sustainability education. It is true that not every method is suitable for some practices, and yet, the participative approach offers significant advantages, particularly in the context of the long-term, school, or community-based projects. In addition to the positive effects on students’ actionable beliefs and competences, the approach provides valid reasons for its worth for promotion among schools, even in light of its possible pitfalls. Lastly, the opportunity for students to participate fits well within the democratic nature of ESE. Based on the deep need to promote democracy in contemporary society (Læssǿe, 2010, Orr, 2022), this approach and may be considered as a more favourable one. To promote its implementation, we should openly discuss its limits, barriers, and possible pitfalls. The participative approach should not be presented as the only way, clearly, the other approaches have their merit and space within the broad stream of ESE. An effort to spread the participative approach in the school environment, however, seems to be one of the main challenges for the ESE community around the world.

References

Baierl, T.-M., Johson, B., & Bogner, F. (2022). Informal Earth Education on Environmental Attitude, Knowledge, and their Convergence. 11^th^ World Environmental Education Congress, 14-18^th^ March 2022, Prague.

De Boeve-Pauw, J., Gericke, N., Olsson, D., & Berglund, T. (2015). The Effectiveness of Education for Sustainable Development. Sustainability, 7(11), 15693–15717. The Effectiveness of Education for Sustainable Development

Bogner, F. X. (1998). The Influence of Short-Term Outdoor Ecology Education on Long-Term Variables of Environmental Perspective. The Journal of Environmental Education, 29(4), 17–29. The Influence of Short-Term Outdoor Ecology Education on Long-Term Variables of Environmental Perspective

Bogner, F. X., & Wiseman, M. (2004). Outdoor Ecology Education and Pupils’ Environmental Perception in Preservation and Utilization. Science Education Journal, 15(1), 27–48.

Činčera, J., & Kovacikova, S. (2014). Being an EcoTeam Member: Movers and Fighters. Applied Environmental Education and Communication, 13(4). Being an EcoTeam Member: Movers and Fighters

Činčera, J., Boeve-de Pauw, J., Goldman, D., & Simonova, P. (2019). Emancipatory or instrumental? Students’ and teachers’ perception of the EcoSchool program. Environmental Education Research, 25(7), 1083-1104. doi: 10.1080

Činčera, J., Kroufek, R, Skalik, J., Simonova, P., Broukalova, L., & Broukal, V. (2017). Eco-School in Kindergartens: the effects, interpretation, and implementation of a pilot program. Environmental Education Research, 23(7), 919-936. DOI: 10.1080/13504622.2015.1076768.

Činčera, J., Simonova, P., Kroufek, R. & Johnson, B. (2020) Empowerment in outdoor environmental education: who shapes the programs?, Environmental Education Research, 26(12), 1690-1706. DOI: 10.1080

Činčera, J., & Krajhanzl, J. (2013). Eco-Schools: What factors influence pupils’ action competence for pro-environmental behavior? Journal of Cleaner Production, 61, 117-121. doi: Eco-Schools: what factors influence pupils' action competence for pro-environmental behaviour?.

Činčera, J., Johnson, B., Kroufek, R., Kolenatý, M., Šimonová, P. & Zálešák, J. (2021). Real World Learning in Outdoor Environmental Education Programs. The Practice from the Perspective of Educational Research. Brno: Masarykova univerzita.

Činčera, J.; Valešová, B.; Doležalová Křepelková, Š., Šimonová, P., & Kroufek, R. (2019). Place-based education from three perspectives. Environmental Education Research, Abingdon: Routledge, Taylor & Francis, 25(10), 1510-1523. ISSN 1350-4622. doi:10.1080/13504622.2019.1651826.

Hart, R. (1992) Children’s Participation: From Tokenism to Citizenship. UNICEF Innocenti Essays, No. 4, Florence, Italy: International Child Development Centre of UNICEF.

Hart, R. (2008). Stepping Back from “The Ladder”: Reflections on the Model of Participatory Walk with Children. In Alan Reid (Ed.). Participation and Learning. Springer, pp. 19-31.

Jickling, B., Blenkinsop, S., Timmerman, N., & De Danann Sitka-Sage, M. (2018). Wild Pedagogies. Touchstones for Re-Negotiating Education and the Environment in the Anthropocene. Springer.

Kendall, S. & Rodger, J. (2015). Evaluation of Learning Away: Final Report. Leeds: Paul Hamlyn Foundation.

Kroufek, R. & Činčera, J. (2021). Metodický rámec pro environmentální gramotnost na školách. Souhrnná zpráva.

Læssǿe, J. (2010). Education for sustainable development, participation and socio‐cultural change. Environmental Education Research, 16(1), 39–57. Education for sustainable development, participation and socio‐cultural change

Lousley, C. (1999). (De) Politicizing the Environment Club: Environmental Discourses and the Culture of Schooling. Environmental Education Research, 5(3), 293–304. doi:10.1080/1350462990050304.

Menzies, L.; Bowen-Viner, K. & Shaw, B. (2017). Learning Away: The state of school residentials in England 2017. LKM. Learning Away

Orr, D. (2022). Education as if People and Planet Matter. 11^th^ World Environmental Education Congress, 14-18^th^ March 2022, Prague.

Ramey, H. L. (2017). Youth-Adult Partnerships in Work with Youth: An Overview. Journal of Youth Development, 12(4), doi: 0.5195/jyd.2017.520

Real World Learning Model (2020). Real World Learning

Rudsberg, K. & Öhman, J. (2010). Pluralism in practice: Experiences from Swedish evaluation, school development and research. Environmental Education Research, 16, 95–111.

Wals, A. (2012). “Learning our Way out of Unsustainability: The Role of Environmental Education.” In: Clayton, S. The Oxford Handbook of Environment and Conservation. Oxford: Oxford university press, 628-644.

Wals, A., F. Geerling-Eijff, F. Hubeek, S. van der Kroon and J. Vader. (2008). All Mixed Up? Instrumental and Emancipatory Learning Toward a More Sustainable World: Considerations for EE Policymakers. Applied Environmental Education and Communication, 7, 55-65. doi:10.1080/15330150802473027.

From this perspective, the Fridays for Future movement can be placed on the seventh rung, as an example of a very high (but still not the highest) level of students’ participation. ↩︎