The Residential District Is Alive

The importance of children’s practical involvement in improving public and green spaces in their cities

Environmentally friendly and climate-friendly—even in the city.

The Czech Union of Nature Conservationists (ČSOP)

01/14 ZO “Natura, quo vadis?” – Eco-centre Malešice, Prague 10

The purposes and objectives of the specific Programme in the context of participatory approaches in education

Our ecological education Programme, “Sparing Nature”, was piloted during the 2021/22 school year as an after-school educational activity for primary school students. The Programme was implemented within the framework of the Regional Action Plan 2, “Innovation in the Education Implementation Programme”, as a Prague partnership between our local Czech Union of Nature Conservationists (ČSOP) grassroots organisation and the Jarov Vocational High School in Prague 9, which provided its detached workplace premises in the Malešice Botanical Garden for the Programme. The Programme instructors and implementers are members of our local ČSOP organisation, which operates in the location where the training took place—the Malešice District (in Prague 10). In the 2022/23 school year, the Programme will be expanded to include the topic of climate change and its prevention in residential district environments.

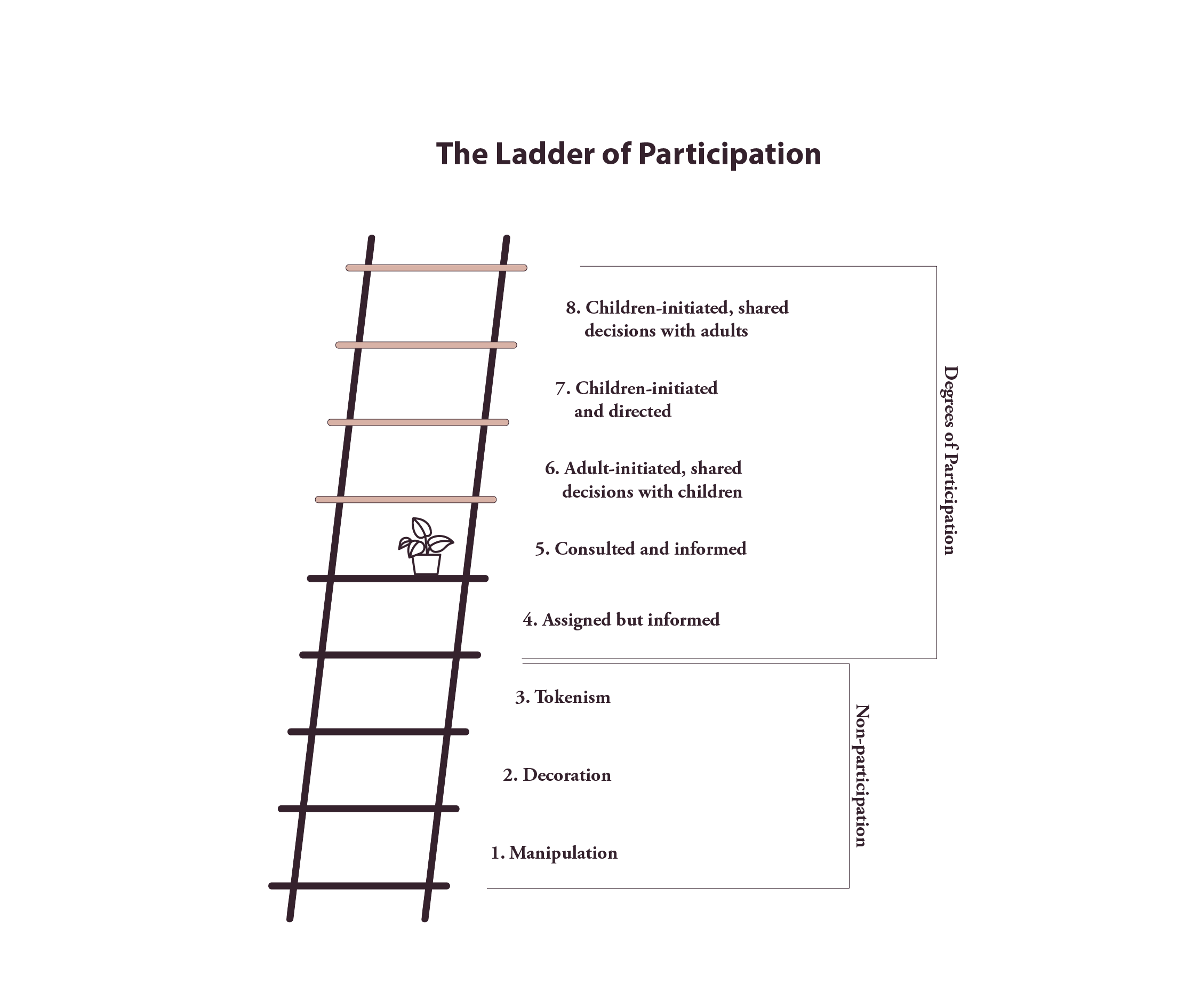

In a playful and popularly-educational way, the instructors showed children concrete examples and procedures for maintaining biodiversity in the city. In our text, we have primarily targeted residential communities, but this is certainly not a prerequisite for the implementation of the Programme. By involving children in practical activities (e.g., forest cleaning, the installation of insect hotels, etc.) and handicraft creative tasks (e.g., the assembly of bird boxes and feeders, the creation of insect hotels, etc.) they are being allowed to gain a real awareness of the possibilities for helping nature within the city in a practical way. They will use their acquired skills and other knowledge, with the assistance of professional instructors, to formulate their own ideas for improving the condition of selected public spaces in the cities in which they live.

Prague is the largest residential district (or, in layman’s terms, the largest City) in the Czech Republic, and at the same time, it is the capital City. Although this Metropolis is one of the greenest cities in Europe, it still faces many environmental challenges (e.g., the accumulation of large, urbanised units prone to heat accumulation, the undeniable effects of global climate change, and the need to adapt the City for future sustainable development) to which both local Government officials and citizens can respond. Gradually, we have learned to moderate the social discussion in a standard way, e.g., in neighbourhood initiatives within the framework of green revitalisation or public space improvements (IPR Prague, 2015). Similarly, it is desirable to involve the younger generations, including even the youngest children, in these participatory processes. The amount of useful suggestions in terms of urban development that can be obtained from children as young as the first grade of primary school or pre-schoolers is often underestimated (Veselý et Stará, 2018).

We consider residential districts to be an important part of cities (and Prague should not be excluded) with many controversies. On the one hand, they are valued for providing practical and relatively inexpensive housing for many inhabitants; while on the other hand, they are often criticised for many partial shortcomings and for their overall urban concept. For their inhabitants, they may seem to be places that do not change much and are, in a sense, familiar and ordinary. It would be illusory to consider Prague’s residential districts as places where time has stopped, however, and all change has ceased. They were gradually affected by processes of generational, social, and technical renewal, and they are still associated with the revitalisation of public spaces today (Hoření Samec et Gibas, 2020).

Historically, residential districts were created based on the modernist vision of living in a green park. Initially, a plan for green space was included in the documentation for the design of residential districts, but unfortunately, due to a lack of financial resources in many cases and the low priority of investment in public spaces, it was only partially implemented. Very few resources were also devoted to their subsequent maintenance schema. This had an impact on the usability of the green spaces and the overall neglect of the residential district environments. Nevertheless, Prague’s residential districts also contain very valuable vegetation species that are worth caring for and developing. Greenery in residential districts provides ecosystem services and integrates the landscape into the residential environment (Orcígr et al., 2020). This urban landscape and green space interface is the best opportunity for public involvement in decision-making for the appearance of public and green spaces to begin. Fortunately, the importance of the cooperation between public administration offices and citizens in matters concerning green spaces (Vejchodská et Louda, 2017) is no longer a matter of controversy today compared to olden times.

The year 1989 was a milestone for the development of Prague’s residential districts as it marked a transition to a market economy. The image of the residential district has changed over the past decades. After a period that is probably most characterised by the reconstruction of the housing conditions and constructions in the residential districts, which was clearly visible from the insulated, colourful facades, there came a period when the demand for improvements naturally shifted from the prefabricated buildings to the outdoors—to the public space (Orcígr V. et al., 2020), around which our Programme is centred. Environmental education aims to strengthen the younger generation’s knowledge of environmental issues while they are also learning to form rational, moral, and emotional processing skills that should be reflected in their opinion, behaviours, habits, actions, and ways of life (Dytrtová, 2014). Similarly, Krajhanzl (2014) understands the relationship between humans and the environment and nature.

An activity for the benefit of the natural environment of the city, whether it is carried out through a school curriculum, an after-school environmental education programme, or through the regular activities of a nature or leisure club, should always provide valuable information that will available for the administrators of the area and be used for the benefit of the site. From our eco-centre’s practical experience, it is important that the greenkeepers are made aware of newly erected bird boxes that will remain in-place after the trees have been maintained. Insect hotels that have been placed around an area, and not only on municipal land, can be used for planning seed-sowing for flowering meadows in the city that will enhance local biodiversity. Children’s activities can thus be directly linked to the practical implementation of local adaptation measures, which must be properly explained and expanded upon during instruction.

Important pillars and ingredients of the Programme

Space

The residential district is somewhere between a “city and countryside” in terms of the type of development and the character of the environment. Most of Prague’s residential districts were located near important landscape areas, and the original concepts often envisaged the recreational use of the landscape. The reality, however, is that they are usually minimally permeable, uncultivated solutions to access the landscapes; they are ultimately inadequate and insufficient facilities in the adjacent landscape. It is therefore necessary, where conditions are right, to see the neighbouring landscape as part of the residential environment of the district, and to develop the relationship and interdependence between the district and the landscape. The “natural” wedges and corridors that run through the districts, which were created for the protection zones of overhead power lines or in the conditions of a waterlogged undevelopable areas, are interesting phenomena that can effectively link the residential district with the surrounding landscape. The surrounding landscape does not have to be merely recreational land. Residential district inhabitants that organise themselves by the tens of thousands and demand contact with their nearest city authorities are effective efforts to lobby for local (small-scale) agricultural improvements and the involvement of residents in public space activities (Orcígr V. et al., 2020).

For our Programme, we used the layout of the Malešice Residential District in the Prague 10 District. The residential district has a direct connection to a large public park, a school botanical garden, and a recreational forest within a walking distance. In addition to the network of streets, all three of these “landscape elements” in the City are connected by a nature trail that shows the historical development of the village and other cultural and natural attractions. We (the authors of this article) are also members of the wider authorial collective of this educational trail of St. Joseph in Malešice.

Topics

It is crucial to not only include the theoretical component in the Programme, but also to promote handicraft production and the students’ own participation efforts in proposals for improving the local climate of the residential to a greater extent, with a view to developing students’ competences and their level of influence on public spaces. In our case we have chosen the following activities:

Practical topics related to the production of material products

- Bird feeders

- Birdhouses

- Insect hotels

Theoretical topics with guided walks and practical demonstrations

- Landscape and the urban environment

- Waste prevention

- Water, you can’t do without it

- The residential district, our home

Practical topics related to the implementation of local adaptation measures against climate change

- Flora: planting a (new) school tree

- Fauna: placing an insect hotel on public land

- The city climate: suggestions for improving (municipal) public and green spaces

We place a great deal of emphasis on material outcomes that students can take away and place directly in their places of residence. We will therefore mention them in more detail. In our case, they are complemented by educational publications that have been produced over the last decade as part of the work of the Prague Environmental Advisory Service.

Bird feeders (Cepák et Voříšek, 2002; Maršálek, 2019)

Feeding birds at a bird feeder is probably the most common and well-known way that everyone can help our feathered neighbours during the colder months. However, even this common activity, including the placement of bird feeders, has its own recommended rules.

Birdhouses (Cepák et Voříšek, 2002; Křivan et Stýblo, 2012; Maršálek, 2018)

In their natural habitat, animals find shelter in tree cavities, earth burrows, or the attics of old buildings. In increasingly modernised cities, however, the supply of these natural shelters, important for reproduction and survival in adverse climatic conditions, is rapidly diminishing. The solution is artificial habitats in the form of birdhouses for birds as well as other animals.

The Insect Hotel (Křivan et Stýblo, 2012; Maršálek, 2020):

If we want to encourage the natural occurrence of insects in gardens and other areas of nature in the city, then we can prepare a place that serves as a shelter for them: insect hotels, houses, and boxes. You can make them yourself; you can buy a semi-finished or a completely finished product (they come in countless variations and sizes). Insects and other related animals are important for the cycle of nature and the ecological relationships within it. They are part of the food chain. They are also essential as plant pollinators.

Participation

The children took the above-mentioned and self-made tangible outputs in the first year of the Programme (feeders, houses, and insect hotels) home with the aim of placing them in the public space around their home (or, if conditions suited, directly in their home). We assume that they carried out this activity together with their parents (instructions for the appropriate placement were given or delivered to each of them). In addition to this, the children left their positive mark on the public space by cleaning up a small area of the local forest adjacent to our residential district. With regard to the other themes (water, waste prevention, biodiversity, and the urban landscape), it gradually became clear that the whole Programme had the potential to engage the children to an even greater extent.

Therefore, we are planning an expansion for the second year of the Programme implementation on the topic of climate change and its prevention in the residential district. Together with the children, we will verify all of the places that have seen small positive changes by placing selected environmental elements from previous activities. With the cooperation of an architectural urban planner, we will identify sites suitable for possible further modifications of public spaces. A short methodological walk with the architect will precede the discussion for gathering children’s opinions on specific improvements. The outputs will then be processed for further use, e.g., by the school, the local authority, or perhaps, the owners of the adjacent areas.

Practical activities with a positive impact on the environment reinforce the role of the individual’s own contribution to the environment from an early age. In addition to practical activities, it is important to let the students be creative in order to make the Programme more fun and fulfilling. The skills and competences thereby strengthened are of an unquestionable importance for the future willingness of individuals to get involved and participate in public affairs.

Risks encountered in the implementation of the Programme

It is necessary to individually assess the potentials and opportunities for the development of a particular residential district and to choose either urban (traditional) or landscape tools, accordingly; this usually involves some degree of a combination of both approaches (Orcígr V. et al., 2020). In the case of our Programme, we are in a very familiar environment regarding our residential districts. However, a trainer may also be exposed to implementing a Programme in a new environment, in which case, a detailed mapping of the situation of the locality is needed.

We agree with the recommendation that the instructors should be strangers to the areas, experienced in the field and in working with children; they should not be teachers from the local school, around whom children tend to self-censor more often. It is essential that the instructor works with a manageable number of children (Veselý et Stará, 2018). In the case of our Programme, it is also necessary to consider and increase the number of instructors for more technically demanding skills and productions.

Concrete impacts on students’ competences

The objectives of the Programme, which are being met with the full involvement and cooperation of the students, should:

- strengthen students’ relationships with their environments and their places of residence;

- strengthen children’s emotional relationships with nature through new knowledge and outdoor learning;

- strengthen the handicraft skills of students, which are generally minimally represented in teaching;

- assist with the implementation of small-scale adaptation measures, especially to enhance biodiversity in cities;

- show the possibility to gain new knowledge for the sustainable development of the residential district from the representatives of the younger generations;

- strengthen relationships among children in an out-of-school setting; and

- strengthen the interactions between children and (grand)parents (in the form of small “home” tasks that use some materials and worksheets).

Impact on the school and the local community

In general, it can be agreed that children are astute observers of the environments around them; they can contribute a lot of valuable information to discussions, including topics that adults would not even realise. The outcomes of the Programme may find applications in city policy documents that deal with the management and revitalisation of public spaces. They can contribute to optimising the offer of leisure activities (often and not only) for children of different ages in different parts of the city. The participation of children also increases the interests of their family members in the topic at hand. Their parents and other relatives, as well as their classmates and their relatives, will learn from the children on the whole. Collectively, this stacks up to a non-negligible number of residents of the localities impacted by the Programme (Veselý et Stará, 2018). The size of the impact on the community increases with the number of students/children who are trained by the Programme and participate fully, or at least partially.

References

Cepák, J. et Voříšek, P., 2002: Zimní přikrmování ptáků, Česká společnost ornitologická [online] [www.cso.cz]

Available from: [http://oldcso.birdlife.cz/index.php?ID=42](Česká společnost ornitologická)

Dytrtová, R., 2014: Environmentální výchova a vzdělávání – textová studijní opora, ČZU v Praze, Institut vzdělávání a poradenství, pp. 43.

Available from: [https://www.ivp.czu.cz/dl/66624?lang=cs](Environmentální výchova a vzdělávání)

Hoření Samec, T. et Gibas, P., 2020: Pražská panelová sídliště jako místa protikladů. In Pražská panelová sídliště jako místa protikladů, Hoření Samec, T. et Michal Lehečka, M. [eds.], Sociologický ústav AV ČR, pp. 1-2.

Available from: [https://www.soc.cas.cz/publikace/prazska-panelova-sidliste-jako-mista-protikladu](Pražská panelová sídliště jako místa protikladů)

IPR Praha, 2015: Koncepce rozvoje veřejných prostranství pražských sídlišť – Formulace základního přístupu. Institut plánování a rozvoje hl. m. Prahy, Kancelář veřejných prostor, pp. 24.

Available from: [https://www.iprpraha.cz/uploads/assets/dokumenty/obecne/krvps_formulace%20zakladniho%20pristupu_male.pdf](Koncepce rozvoje veřejných prostranství pražských sídlišť)

Krajhanzl, J., 2014: Psychologie vztahu k přírodě a životnímu prostředí. Lipka a MUNI Brno, pp. 200.

Křivan, V., et Stýblo, P., 2012: Živá zahrada. Chaloupky, o.p.s. a Český svaz ochránců přírody Kněžice, pp. 70.

Maršálek, M. [ed.], 2018: Jak podpořit živočichy ve městě aneb budky ptačí i jiné. ZO ČSOP Natura, quo vadis? a EkoporadnyPraha.cz, osvětový leták.

Available from: [https://natura-praha.org/documents/budky-ptaci-i-jine.pdf](Jak podpořit živočichy ve městě aneb budky ptačí i jiné)

Maršálek, M. [ed.], 2019: Zimní přikrmování ptactva ve městě aneb ptačí krmítko. ZO ČSOP Natura, quo vadis? a EkoporadnyPraha.cz, osvětový leták.

Available from: [https://natura-praha.org/documents/ptaci-krmitko.pdf](Zimní přikrmování ptactva ve městě aneb ptačí krmítko)

Maršálek, M. [ed.], 2020: Hmyzí hotel. ZO ČSOP Natura, quo vadis? a EkoporadnyPraha.cz, osvětový leták.

Available from: [https://natura-praha.org/documents/hmyzi-hotel-2020.pdf](Jak podpořit hmyz ve městě)

Orcígr, V., Babišová, M., Havlová, N., Hronová, M., 2020: Adaptace na klimatickou změnu v prostředí měst: strategie, rizika a dobrá praxe (případová studie). In Urbanismus a územní rozvoj, Vol. 23, No. 3, pp. 18-26.

Available from: [http://www.uur.cz/images/5-publikacni-cinnost-a-knihovna/casopis/2020/2020-03/03-adaptace.pdf](Adaptace na klimatickou změnu v prostředí měst: strategie, rizika, dobrá praxe (případové studie))

Vejchodská, E. et Louda, J., 2017: Partnerství obcí s veřejností při správě městské zeleně. In Urbanismus a územní rozvoj, Vol. 20, No. 3, pp. 10-14.

Available from: [http://www.uur.cz/images/5-publikacni-cinnost-a-knihovna/casopis/2017/2017-03/02-partnerstvi-obci.pdf](Partnerství obcí s veřejností při správě městské zeleně)

Veselý, M. et Stará, K., 2018: Jak mohou děti přispět k tvorbě příjemnějších a bezpečnějších měst? [online] www.estav.cz

Available from: [https://www.estav.cz/cz/6290.jak-mohou-deti-prispet-k-tvorbe-prijemnejsich-a-bezpecnejsich-mest](Jak mohou děti přispět k tvorbě příjemnějších a bezpečnějších měst?)