School For Sustainable Living

A school that actively changes its surroundings, helps students form a relationship with place, gives students a voice, prepares them for real life, is open to the community and changes the world for the better

“The way I understood the project was that I was inspired by the teacher at the introductory seminar who said that she was going in with a clean sheet of paper and the children were doing everything. I also try to let the kids invent everything and it makes them so happy when they get something right. So I try to interfere as little as possible, and even though they’re in the sixth grade, they’re capable — they can communicate with the principal, they’ll go to the cooks in the school cafeteria, they‘ll talk on the radio, and they get joy out of all of it.”

Eva Kučerová, Elementary School Býšť’, second grade teacher

What you can learn about the Programme

- What the School for Sustainable Living is, what it aims to achieve, and what it can bring and to whom.

- What works in guiding the Programme and communicating with teachers so as to enable the students to decide how the Programme will run and what can come out of it to the greatest extent possible for that teacher or school.

- Which recurring situations are at risk in the Programme.

Teachers and students can choose to focus on climate change or sustainable living in the community as part of the School for Sustainable Living (SSL, or ŠUŽ) Programme. On the topic of climate change, they cooperate in learning ABOUT a place and IN a place (by mapping the problems and needs of the municipality in terms of climate change); they do something FOR a place together (by planning and implementing practical local projects to mitigate the causes or impacts of climate change in the municipality); and they search THROUGH a place for connections (between a place and climate change).

Within the theme of sustainable living, students and other partners think about what they can do to develop their community or school neighbourhood. Together, they then implement the proposed changes one-by-one, learning something new and changing the place where they live for the better at the same time.

In most cases, the Programme is implemented by one class (rarely across grades or within an interest group — a club). The North (SEVER) Horní Maršov Centre for Environmental Education is the group responsible for implementing the School for Sustainable Living Programme in regular classes so that all students have the opportunity to go through the educational process offered by the SSL (ŠUŽ). The Programme with a focus on climate change has proven to be successful for 8^th^ and 9^th^ grade students as well as students in secondary schools, and the Programme focusing on sustainable living can be implemented across all school levels.

The Programme is most often implemented in small municipalities. The school is the focal point where ideas are generated and then disseminated through parents and grandparents to the community and village leadership. Through the Programme, the latter learns about the importance of openness of the authorities to children. In small communities, personal links are usually established with the council (one of the parents of the children involved; the teacher involved in the Programme). There is also a valuable experience with small or medium-sized towns (up to about 40,000 inhabitants) where students and teachers focus on a particular locality they are mapping. Each year a school from one regional town gets involved. In this case, it is advisable to define the boundaries of the area (e.g., urban district) within which the students will focus.

The NORTH (SEVER) Centre aims to connect the initiative of children and young people with the events in the village. We use the potential of participation of students who, with the support of teachers, create local climate action plans or visions for a sustainable community in their villages and then implement the adaptative, mitigated, and sustainable measures.

Programme sub-objectives

- It should strengthen children’s and youths’ beliefs about the possibility of making their own impact on climate change and overall sustainability efforts.

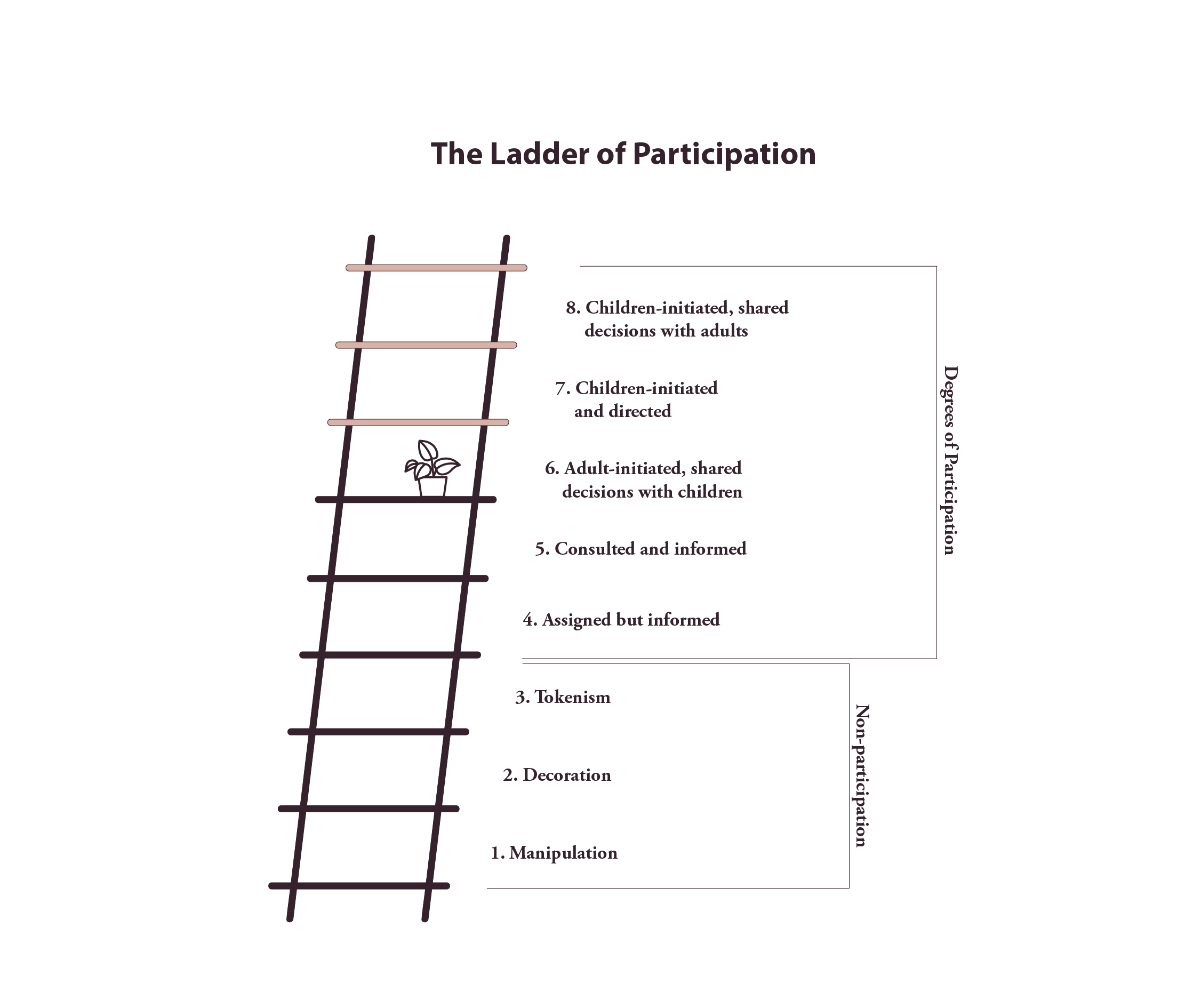

- Civic education should be developed for children and young people, the local government, and educators through the use of participatory methods.

- It should cultivate a greater understanding among the local government, educators, other stakeholders, and the public of the importance and benefits of civic engagement with children and young people.

- It should promote a greater understanding among the local government, other actors, and the public of the urgency and opportunities to address climate change and sustainable community development.

- It should encourage the participatory (child and youth-initiated) planning and implementation of action plans, community visions, and a follow-up at the local level.

Eight points that have worked well for us when communicating with teachers about the Programm

1. Sharing examples of best practices among teachers and students

At the introductory seminar for newly-recruited teachers, teachers speak together with students who have already completed the Programme. The students present what they have experienced in the Programme, what it has brought them, what they have learned, and what they would not have otherwise learned , known, experienced, etc. Teachers present what they faced and what helped them, what came out of the Programme, and what motivated them to carry the Programme through to the end.

2. Small solutions are fine

Teachers often have questions about what the outcomes should be. The consultants who guide them through the Programme have concluded that it is impossible to determine because the principle is that the students create the outcome. Nevertheless, it has been useful to share projects from previous years to give a better idea of what is possible within the Programme. It is also important to note that it does not have to be a “big project” (e.g. a workout playground); all the little things that come up from an adult perspective count, like a rainwater tank in the garden, Fill Your Tank stickers placed in cafes and institutions around the town, a clothing-swap bazaar, a vegetarian Wednesday in the school cafeteria, a thoughtful lawn-mowing initiative in the village, improving the plaza in front of the school (e.g., replacing the pavement), etc.

3. Good methodology

Teachers receive a set of methodically-described activities for teaching from the NORTH (SEVER) Centre. They can use the methodology as a “cookbook” and implement the activities exactly according to their descriptions. They also have the possibility to adapt the activities to the school climate, to students’ knowledge, skills, and experiences, or to their own teacher perspectives. The important thing is to meet the objectives of the different steps of the Programme to ensure their continuity. The activities described serve as a guideline or a kind of safety net for some, but they are not an obligation, as teachers are also participants in the whole Programme and must be able to adapt the activities to their own capacities.

4. Reliably successful facilitation techniques and forms

In addition to the recommended activities for the classroom, there are also tools to reassure teachers that these activities are tried and tested with reliably successful results where students can select/develop intentions that will have impacts and be actionable; for example:

- The selection and elaboration of final projects: the feasibility and impact table for selecting the project to be implemented, or a paper method to involve everyone in the design of activities, etc.

- A task book: a ready-made structure for how to divide up tasks to finalize and finish the work.

- A list of suggested questions to ask at community meetings; how to prepare for meetings with councillors, etc.

5. Trained consultants

The consultant is the teacher’s right-hand-man: they are their guides. They should ask the teachers questions (they have monthly consultations to assess how things are coming along, where teachers are at in their processes, etc.); they should know that the conditions are different in every school, and they should stress that the project should remain in the hands of the students (even if they suspect that the teacher wants to improve the bus stop, for example).

6. Ongoing student and teacher sharing meetings

Sharing is the main core of the Programme. In the course of the project, teachers and students should meet (possibly online) to reflect on the progress of the Programme according to the questions asked; they should share opinions and visions of what lies ahead and enquire if anyone is dealing with similar problems. In doing so, they all have the opportunity to share with each other the problems and joys of the project they have chosen.

7. Final celebration

The recommendation of the NORTH (SEVER) Centre is to organise a joint closing (appreciation) event in the village and encourage everyone to participate from the village, students, parents, and even the consultant. This will make it clear that the whole process and what has emerged is important.

8. Necessary reflection

From an educational point of view, evaluation (reflection) of the entire process is the most crucial step. The students, together with the teacher and through reflective questions, first communicate their feelings: when they were happy, when they were scared, when they were uncomfortable, etc. Then they go through all of the activities again and arrange them in a logical sequence, recalling what they experienced during each phase. At the end, each student should draw their journeys through their selected projects using symbols that should include questions to reflect on for the future.

Risk situations that teachers face in the Programme and how to prevent them

“I go in with a clear idea of what I want to do.” Teachers decide what the outcome at the end should be and then go through the learning and planning process with the students, but more as a formality to meet the requirements of the Programme. In the final stages, they present their proposals to students: the “undeniable " advantages therein, why they believe it should be implemented, and why the students should accept it by default. There’s also a similar situation that can occur where students lose control of the project in the final stages, after a long period of participation in the whole process; they are presented with limitations around why what they have chosen cannot be implemented. The limitations may be presented by the teacher and the municipal administration (e.g., “it is not on municipal land,” “it would cost too much money,” we have other plans for the site,” it should be solved by experts,” etc.)

Instead, teachers and educators have the opportunity to connect with a trained consultant who believes in the Programme and its concept of participation, has experience in other schools, knows their specific school conditions, and can help navigate teachers through the Programme so as to keep it in students’ hands and under their control as much as possible.

“I don’t have the skills and experience to facilitate participatory learning, and I don’t have the tools to do so; I don’t consider it important to spend time and energy learning participatory approaches.” This is not the fault of the teachers themselves, however, because they are generally not encouraged to adopt participatory approaches in Czech faculties of education; and at the same time, they have not acquired the habit of taking failures as necessary conditions for innovation and to try new methods.

Teachers have access to a set of materials, activities, recommended practices, and a list of questions to encourage participation and guide facilitation. They can try them out in the Programme workshops and then share their experiences with other teachers.

“I am concerned about undertaking more conflicting projects with students, and therefore tend to steer students away from such topics.” This can affect students’ beliefs about whether or not their efforts, ideas, and attitudes can make a difference. It is also necessary to be able to work with the different attitudes and opinions of the various actors in different states as well as with possible failures, and this can be challenging for teachers in terms of their experiences and general lack of evidence.

The methodology, which they may discuss with a consultant or read through, step-by-step, contains recommended procedures, a list of questions, and model situations that can lead to preparation for the meetings with the municipalities or communities. It can also guide teachers through the subsequent reflection of such an event, including students’ reflections on their own feelings.

“I most often implement the Programme alone; seldom in pairs, and very rarely in collaboration with other teachers in the school.” Cooperation among teachers is very important. To a certain extent, SSL (ŠUŽ) can be used in all subjects, not only in the more usual options, such as science, geography, history, or civics. The Programme cannot do without mathematical, linguistic, and even artistic skills, which are related to the outcomes that are produced in the community or the school thanks to the SSL (ŠUŽ).

You can use the materials in the Programme to help with collegial support (how to build a team, how often to meet, how to set goals and evaluate them, etc.). A strong recommendation at the beginning of the Programme is to pair at least two people together and task them with being supportive of one another; let management and colleagues know what is going to happen and what is expected of them; and to keep management and colleagues informed about the progress of the selected projects, etc.

In a 2018 evaluation of the Programme, it was concluded that:

- Students and teachers are mostly satisfied with the Programme and rate it as a positive experience that they would like to repeat.

- The Programme is likely to have strengthened inter and intrapersonal competences of the students, especially their ability to work together as a team and communicate their views. It also had a positive impact on classroom relationships.

- Teachers and students perceived the Programme as participatory. Overall, students perceived the Programme as participatory and community-oriented. Most of them believe that their outcomes helped to change something for the better in their villages.

- The students themselves saw the benefits of the Programme, mainly in the development of their own cooperation and class bonding. This was reported by respondents from all focus groups.

“For example, I learned that it’s good to work with everyone, not just one person.”

A primary school second-grader

To a lesser extent, students also reported other benefits, in particular a deepening of their knowledge and interest in their communities or a sense of empowerment to influence their environments.

“I learned that even children can do great things.”

A primary school second-grader

Teachers see the benefits of the Programme for students in three areas:

- The most frequently cited impact of the Programme was the positive effect on classroom relationships.

- Some teachers also assume that the Programme helped to develop students’ interpersonal (cooperation, communication) and intrapersonal (self-esteem, responsibility) competences.

- Finally, the last area of benefit, according to the teachers, was the strengthening of the students’ relationships within their communities, including increased senses of belonging and understanding of community function.

The students expressed themselves differently while they were working on their projects within the Programme than they otherwise would in a regular classroom; teachers also have more opportunities to get to know students better. This way of teaching allows children, who otherwise rarely experience a sense of achievement, to excel.

“During the normal lessons, the girl was typically working more slowly, but thanks to her extraordinary attention to detail and patience, [in another type of lesson] she was able to craft each detail of the ornament perfectly.”

Sofie Hladíková, a first-grade teacher at Kocbeře Primary School

The Programme positively influenced teachers’ beliefs about their abilities to teach in a participatory way, or in a way that connects their teaching practices to the community and helps to develop students’ competencies for sustainability in educative practices.

In most cases, the municipality, the community, and the school management were very appreciative of the students’ work during the Programme, and they support students’ ideas; however, as previously mentioned, when it came to project implementation, they often attempted to persuade students to implement simpler, more beautifying measures (i.e., not necessarily students’ own conceptions).

The Programme is based on cooperation with the community, therefore students involve the community at the very beginning of the Programme during their mapping processes of the community from the points of view from different target groups; they created surveys and went around town to speak with the citizens about their suggestions as well as consult with parents and grandparents.

Often times, parents or grandparents have been involved in the implementation of the Programme and were participants in the teaching process as community experts; they helped during the planning and actual implementation phases. The sponsorship of some of the implemented measures was also a frequent occurrence, either by parents, funds from the municipal budget, or the involvement of a local business.

Teachers are often supported by the management, and this gives teachers the confidence and space to implement the Programme more successfully. In fact, the schools visibly contribute to the improvement of the environments in cities; schools’ management teams often appreciate this practical aspect as reflective of a school’s prestige.

“The children are working together creatively to produce something that is part of the school’s visible reputation.”

Dušan Vodnárek, Vrchlabí Primary School