Those Who Adapt

How to participate with children at the community level vis-à-vis measures of adaptation to climate change in residential districts

“The children especially liked the fact that it was about their city and that they learned some extra information. They could come up with their own ideas about what they would do in their city.”

A primary school teacher

Presentation of the Programme

- You will be introduced to a Programme using community-based and semi-participatory (blended) approaches to learning that involve students in decision-making at the community level.

- You will learn what obstacles are encountered in the implementation of the community-based learning approach in the Czech environment and how to prevent and overcome them.

- You will become familiar with the Programme using other modern teaching methods, especially research-oriented teaching, simulation games, online applications, field teaching, and team and group work.

The purpose and objectives of the Programme in the context of participatory approaches

The first basic goal of the Programme is for students to gain knowledge and skills about which adaptation measures can be taken in the city where they live and how they should behave in case of negative effects from climate change (e.g., floods, torrential rain, drought, high temperatures, or extreme weather events like ice storms or wind storms). The second basic objective is to strengthen the relationship with and responsibility for the places where students live and their readiness to act in favour of the environment. Students get to know key actors in their community and hold discussions with them about the need for adaptation of the community to climate change and the appropriate adaptation measures. In this way, the Project allows for building long-term relationships among the school, the municipality, local organisations, and fellow citizens.

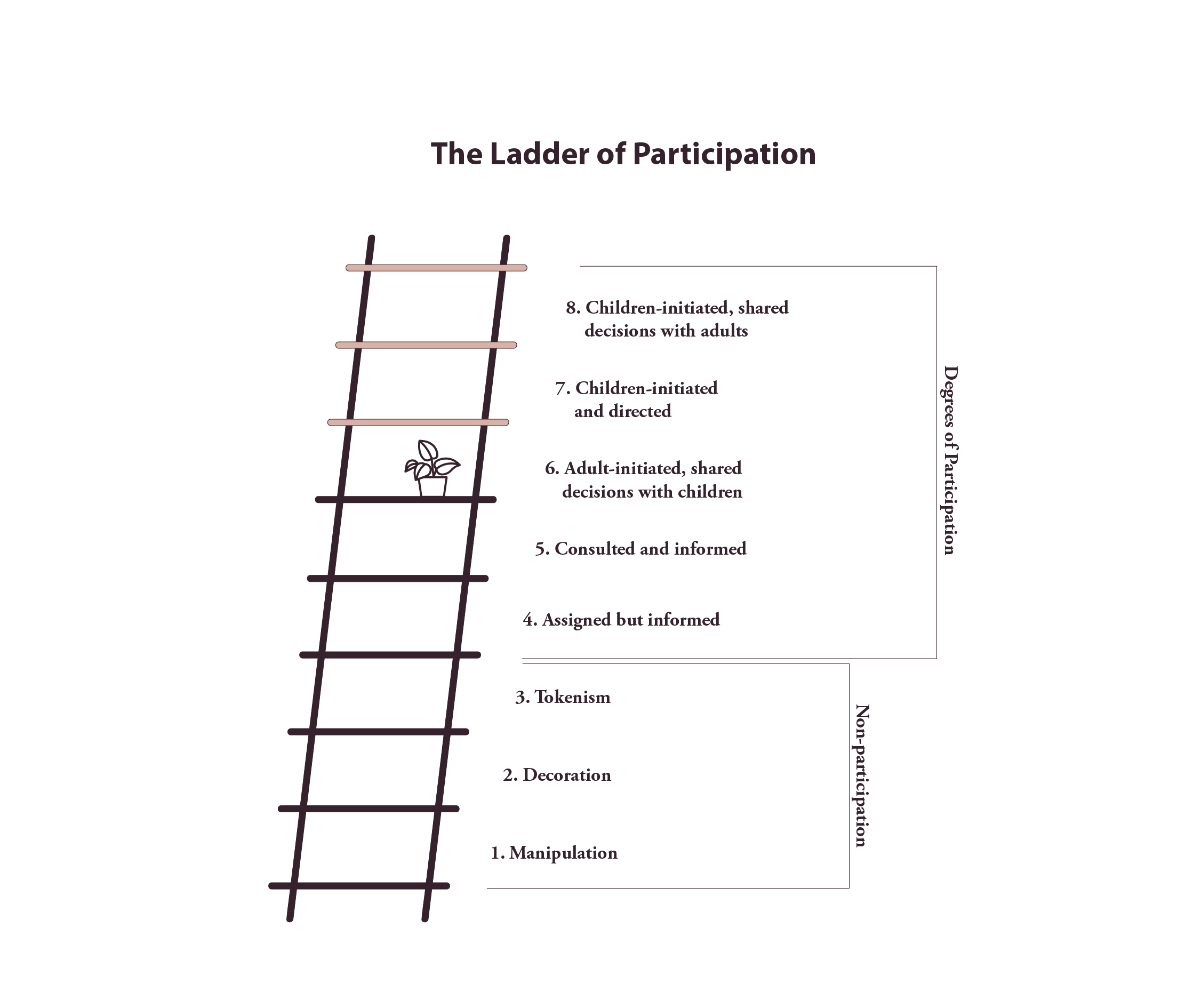

The Programme takes the form of a blended learning approach, combining an instrumental approach with elements of an emancipatory approach. While the first part of the Programme (Block 1 or Block 5) is conducted in a more instrumental way, the second part of the Programme (Blocks 2 through 4) contains emancipatory elements, especially in the form of the choice of adaptation measures, their presentation, and the means of implementation.

The brief contents of the Programme

Students will:

- acquire knowledge on climate change and skills in adaptative measures;

- be able to identify suitable adaptation measures in the vicinity of their school or on school grounds;

- present their proposals at a local adaptation forum where representatives of the community, experts, officials, and other key stakeholders will be present;

- discuss their proposals, as those that will be judged to be the most necessary, realistic, and well-presented will receive funding for the implementation; and

- implement the proposed adaptation measure(s).

Important pillars and ingredients of the Programme

The implementation of a “local adaptation forum” involving public administration representatives, local authority officials, citizens, and other key actors from the municipality (e.g., NGOs, companies, and schools) is an important pillar. Ideally, the Project should be implemented in parallel with the preparation of the local adaptation strategy so that the students’ proposals become part of that plan. In this way, it is possible for students to implement their proposals conceptually and gradually over a period of several years. The Project can become part of the school curriculum and be implemented over a long period.

The key functioning behind this pillar is the implementation of the adaptation measure itself. If students do not get the funding necessary to implement a “difficult” adaptation measure, then they should at least try to implement a “soft” adaptation measure; this can lead to either public awareness or, in the best case, to raising the funds required to implement the more expensive adaptation measure that they initially selected. Students can organise a fundraising event at school for fellow citizens or try, for example, to approach local businesses to ask for donations. The students’ own actions on behalf of their environments are key to their beliefs in their own environmental impact and willingness to remain engaged in public affairs. It is not enough for students to simply think of appropriate adaptation measures and leave their proposals on paper, as this can lead to demotivation and a reluctance to engage in future projects.

It is also important to prepare students well for possible setbacks or complications when communicating with public administration representatives. In the context of research activities, it is advisable for students to choose for themselves which group of professionals (e.g., urban planners, researchers, mathematicians, etc.) they would like to communicate with in terms of their own abilities, skills, and interests. When selecting students’ proposed adaptation measures in the local adaptation forum for the whole class, it is important to respect democratic principles, listen to all suggestions, and agree on the voting methods in advance. For the presentation of the adaptation proposal, it is necessary to select students who are the most interested. The proposal is then presented by a selected team of active students; their peers may (or may not) be present in the auditorium and they may add to the presentation or respond to it in the discussion.

Similarly, it is appropriate that Block 4 – the actual implementation of the adaptation measure – should be carried out by the students as a voluntary activity. The timeframe for Block 4 is not clearly defined, as it is up to the school or teacher to decide how much time they would like to devote to the actual implementation phase of the adaptation measure; for example, if a class receives money for the implementation of an adaptation measure from the county or municipality and then decides to buy a tree and plant it together, then the whole Block may take up to 4 lessons. If the class implements a softer measure, however, in the form of an awareness campaign or a fundraising event, for example, then Block 4 may take much longer to implement fully. Another important pillar of the Programme is composed of the well-prepared and detailed methodologies, materials, and worksheets for Blocks 1, 2 and 5. The teacher should determine in advance whether they want to include optional activities from Block 5 in the Project, and then they should study all the materials well. For some of the more challenging specialist topics, teachers may seek help from experts from universities, research centres, eco-centres, and environmental education centres dealing with climate change and adaptation. Teachers should consider well in advance whether they want to carry out the Project with their students on their own or through assistance from one or more of the above-mentioned sources. They can also join forces with other colleagues from the school and make a school-wide Project (some topics can be taught by the mathematics teacher while others by the chemistry or civics teacher).

The negotiation phase for a particular implementation of a suitable adaptation measure on land owned by a municipality or a private person can be assisted by the staff of the local eco-centre or environmental education centre; this assistance is advised, as these professionals often have experience in involving municipalities in other projects and can provide or recommend a suitable moderator and facilitator for a successful meeting between students and public representatives of the municipality.

What were the main success factors of the Project?

- One of the key success factors in the implementation of the Project was that the individual Programmes were delivered to the given age groups in a way that was proportionate to their age; students in grades two through nine undertook practical activities that took place partly in outdoor environments. These practical activities were connected with other attractive activities (e.g., board games, interactive applications, thermal imaging cameras, etc.) and active teaching methods. Due to the alternating nature and variety of the activities available, each student was able to find an activity that was interesting to them.

- The methodological materials and aids (their contents and graphics) were another factor that contributed to the success of the Project, as they were complete, accessible, and informative.

- A significant factor in the success of the Project was the competition among and presentation of the proposals at the local adaptation forum, thanks to which the students were able to attract funding for the implementation of the most important adaptation measures that they selected on their own.

- The most important success factor was the ability to implement the proposed measure(s).

- The friendly and sensitive approach of the lecturers also played an influential role in the success.

Which factors limited the success of the Project?

- Two of the factors that negatively affected the progress and results of the Project were time and inclement weather; often it was not possible to stall the process to wait for the rain to end.

- In the Czech school environment, teachers often struggled with the lack of time for project-based learning due to the pressure they’re already under from the amount of materials and topics they have to teach their students. Similarly, in the second grade of primary schools and high schools in the Czech Republic, where students spend each lesson with a different teacher, it is problematic to arrange the logistics of the Project with regard to the organisation of other classes due to the teachers’ dwindling availabilities to implement the Project. Also, at least fieldwork requires at least two teachers to be present, so it is difficult sometimes to retain a second teacher for the Project (this is where staff from eco-centres and environmental education centres could help).

- Challenging topics for students: some challenging topics are very broad and difficult to fit into a limited timeframe (see time above).

Evaluation by teachers

- Teachers perceived that the Programme had a positive impact on students’ relationships with the places where they live.

- In the overall evaluation of the activities in the questionnaire survey, teachers gave positive feedback.

Evaluation by students

- In the overall evaluation of the activities, students rated the Project positively.

- The students appreciated the alternation and variety of activities, as everyone was able to find an activity that they personally enjoyed; they appreciated that they not only took away a wealth of knowledge from the Programme, but also various additional skills, especially in the sense of teamwork and cooperation.

Risks encountered in the implementation of the Programme

Our experience is based on the pilot implementation of the Project in Prague from 2014 to 2017. During the evaluation of the Project, it became clear that in contrast to the citizens, local NGOs, and companies that communicated willingly with the students, the communication with City district authorities (of Prague) appeared problematic. As a rule, teachers and students contacted the staff of the environmental department at the municipal district office by e-mail or post. In the letter, they briefly introduced themselves and the Project and asked for help in identifying problematic sites. In the vast majority of cases, however, there was either no reply or the response was dismissive or even derisive. This led to demotivation amongst the students. Other districts got involved in the Project mainly thanks to personal contacts, such as a teacher who was also the Chairman of the Environmental Committee at the local authority that year, and the mother of one student who worked as a clerk at the local authority.

Recommendation:

Discuss the possibility for setbacks or complicationswith a particular authority ahead of time with students.

We have another negative experience with the authorities from the pilot version of the Project, which was implemented between 2015 to 2016 in three Czech cities. All three cities agreed to present the students’ outcomes to a panel of evaluators to be selected from city councillors and officials; and this selection was to be carried out by mayors, deputy mayors, or other office staff to whom the responsibility would be delegated. The evaluators themselves were briefed on the contents of the Project as well as the agenda for the students’ presentation for the council. The students’ presentation at the municipal offices was best received in Žďár nad Sázavou, where the councillors listened to the students and praised them for their work, which they found useful. The students’ proposals then became part of case studies on municipal adaptation to climate change impacts (adaptacesidel.cz.

By contrast, in Hradec Králové, the students’ presentation to the representatives was an unpleasant experience for the students. According to comments made in interviews with their teachers, the representatives and officials were unpleasant or reacted inappropriately to the students. They tested the students on their knowledge (the questions assumed students should already possess a university-level knowledge of science) to demonstrate their stance that the students lacked the necessary competences to contribute towards decision processes regulating the green and public spaces of the municipality. Furthermore, officials’ defensiveness against the implementation of students’ proposed adaptation measures was palpable, which was thought to be due to the presence of a superior official and a political representative. Although the activity was discussed and the village councillors were made aware of its objectives, the failure to acknowledge students’ proposed implementation measures as valuable was likely due to internal disagreements and a chaotic situation in the particular office; officials who were sent to the meeting were probably not properly familiar with the Project.

Recommendation

- Schools and children should be partners and important teammates for community adults.

- While students’ suggestions are not meant to replace expert opinions, they can still be inspiring, motivating, and activating for their communities.

- The aim is mainly educational; it is about educating students and preparing them for civic life, because students will best acquire civic and environmental competences by engaging with their local communities on the problems that their municipalities are solving.

- Students need to be prepared for possible negative reactions from representatives of public administration offices and their official structures.

- Centres for environmental education, which often have experiences in involving municipalities in other projects, can help negotiate the necessary cooperation and provide or recommend a suitable facilitator for a successful meeting between students and public representatives of the municipality.

Competences that the Programme encouraged students’ development

- Relationships with the places in which they live (where their school is located)

- Increased willingness to act on behalf of the environment in their area

- Further knowledge and skills in climate change and adaptation measures

- Additional research skills and knowledge

- Cooperative skills

- Presentation skills

- IT skills

Impact on the school and the local community

In some cases, it was possible to establish longer-term cooperation between the school and public administration representatives as well as maintain contacts with interesting key actors (e.g., with Fridays for the Future). Sometimes it has been possible to involve students’ parents and fellow citizens. Some schools run the Project on an annual basis, which allows us to continually push and strengthen the Project.

Terminology

- PARTICIPATIVNÍ PŘÍSTUP: Metodický text pro studenty učitelství

- KOMUNITNÍ PŘÍSTUP: Metodický text pro studenty učitelství

- O globální změně

- Badatelé

About the Programme

- The Programme was awarded the 2019 EDUína Award for Innovation in Education (3^rd^ place) under the title “City Builders”.

- Further information about the Programme

- Detailed Programme methodology